Imagine facing a multi‑billion‑dollar giant with roughly 9,000 stores when all you have is a small team, a simple website, and a stack of DVDs in a warehouse. That was Netflix in 1999, staring down Blockbuster’s market dominance.

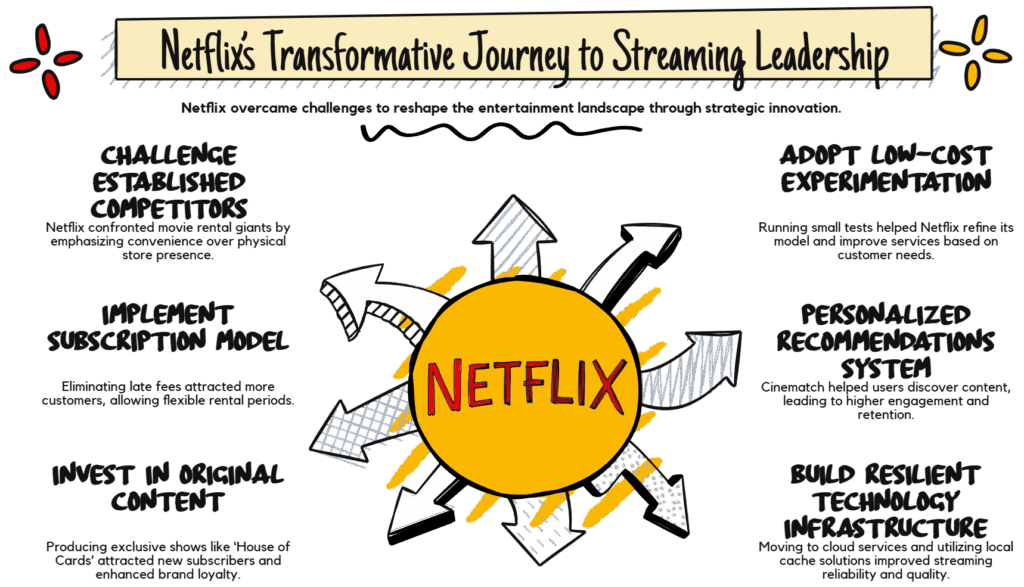

In this article, you’ll see how a series of bold choices helped them not only survive but transform the entire entertainment industry. We’ll map those choices into three repeatable tactics you can use when your organisation faces disruptive change—identifying early signals, running low‑cost experiments, and reshaping customer habits.

It all started with a single decision that could have ended Netflix before it began.

The Call to Adventure

Around 2000, Netflix’s founders found themselves in a meeting that could have changed everything. On the table was an offer to sell the company to Blockbuster for $50 million.

At that point, Netflix was still relatively unknown, operating on thin margins, and facing an entrenched competitor with thousands of stores nationwide. Accepting would have meant folding into Blockbuster’s brand and losing its independent identity. They declined the offer and went on to continue independently, a choice that removed any fallback and forced the team to find a way forward on their own terms.

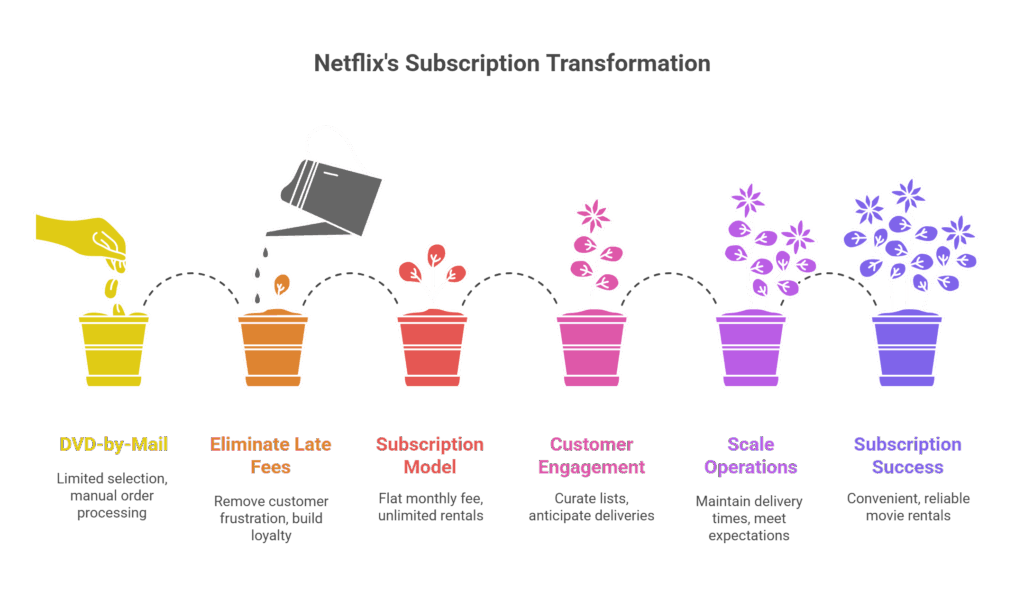

Just a few years before, in 1997, Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph had begun experimenting with the DVD‑by‑mail concept.

This wasn’t the product of years of detailed market studies or a large launch budget. DVDs were a new format for most households, and the idea of ordering movies through a website was unfamiliar to the average customer.

Their first site existed mainly to process basic rental transactions—there was nothing especially polished or powerful about it.

What they did have was a willingness to run small experiments to see if any approach clicked with customers. Decisions were driven by testing, learning, and adapting rather than following a fixed master plan.

Compared to traditional rental chains, the odds didn’t look favorable. Blockbuster and its peers had thousands of high‑visibility locations, heavy advertising across television, print, and direct mail, and a customer base trained to expect immediate in‑store pickup.

For Netflix, asking people to wait a few days for a disc to arrive in the mail meant asking them to alter a routine that was as ingrained as picking up groceries.

Inside Netflix’s first warehouse, the limitations were clear. It was small enough to cross in seconds, with rows of DVDs on shelves and employees preparing orders by hand.

Order slips were printed, discs were inserted into red envelopes, sealed, and placed into bins for postal pickup. There was no automation—just manual processes that met the immediate need while keeping costs low. That’s your cue as a manager: start cheap, learn fast—use low‑cost manual hacks to validate the idea before automating.

The focus during these early years was survival through rapid iteration. Some weeks they experimented with packaging to reduce mailing costs without damaging discs; other weeks they adjusted selection to better match demand. It was a cycle of trial and refinement, guided by customer response. This deliberate, iterative approach allowed them to adapt quickly instead of committing prematurely to expensive systems that might not fit.

One of the clearest pain points they noticed in the broader industry was late fees. Competitors relied heavily on them for revenue, but customers saw them as arbitrary penalties. Research shows that these fees triggered resentment, damaging loyalty even when they brought in short‑term income. Eliminating late fees could remove one of the biggest sources of negative sentiment toward rentals—and that insight opened the door to a bold experiment.

In 1999, Netflix introduced a subscription approach, followed in 2000 by its “Unlimited Movie Rental” option. Instead of charging per rental, customers could pay a flat monthly fee and receive as many DVDs as they wanted, mailing each one back to receive the next from their queue. There were no due dates and no late fees—subscribers could hold onto a disc for two days or two weeks without penalty. It was a model built not on punishing slow returns but on encouraging steady engagement.

The subscription shift carried risks. Higher shipping costs and slower turnover from some customers could outweigh the benefits if not balanced by others who cycled quickly through titles. Stock had to be sufficient to satisfy different tastes and viewing habits. But it gave Netflix a proposition no store offered: convenience without the anxiety of added charges.

Early adopters responded positively. Without the threat of late fees, the perceived risk of trying the service dropped. Customers began to enjoy managing their queues online, anticipating the arrival of the familiar red envelopes, and setting their own pace for watching. Some kept DVDs for extended periods, using them more like part of a home library before moving on. At the time, this was a major break from the established rules of the rental business.

Behind the scenes, manual labor still dominated operations, and subscription growth meant more shipments to prepare. But the change was beginning to create steady, predictable demand that even Blockbuster’s far‑reaching marketing couldn’t erase. Netflix had found an opening by removing a frustration rather than replicating its rival’s strengths.

Strategically, tying revenue to customer satisfaction created a sustainable advantage. The longer subscribers stayed happy, the more profitable each became. This was the opposite of the store‑based model, where revenue could rise from actions that upset customers in the moment, like charging late fees. By aligning its success with customers’ positive experiences, Netflix was quietly building trust.

The subscription model also began shaping consistent user habits. Subscribers curated personal film lists and tracked what they had watched. Anticipating the next delivery became part of their weekly routine. By making the service a consistent presence in customers’ lives, Netflix increased the effort required for anyone to switch away—not through contracts, but through the convenience and familiarity of the process.

Although this first leap didn’t guarantee dominance, it established a foundation. Netflix demonstrated it could compete by redesigning a key aspect of the experience rather than battling on store count or ad spend. Word spread as satisfied customers shared their experiences, gradually expanding the subscriber base.

From the inside, the emerging challenge was scale. Maintaining consistent delivery times, keeping discs in good condition, and meeting expectations in both large markets and remote areas would require more than just adding people or stock. It would demand systems and technology capable of handling growth while preserving the reliability and trust that the model depended on.

The decision to remove late fees and go all‑in on subscriptions was the first in a chain of calculated moves that reshaped how movie rentals worked. As each operational and customer‑facing improvement built on this base, Netflix strengthened its ability to stand out in a crowded market. Those plain red envelopes were not just packaging—they were evidence that a small, well‑timed adjustment could shift customer behavior in lasting ways.

Which brings us to the real test: changing habits that millions of people followed without thinking.

Crossing the First Threshold

Changing that kind of behavior meant directly challenging a long-standing ritual. For decades, watching a movie at home started with a trip to a brightly lit rental store, walking rows of shelves, scanning covers, and making a choice after holding the case in your hands. That wasn’t just a step in the process—it was part of the enjoyment. Many assumed it was too entrenched to replace. Netflix’s unlimited subscription removed late fees and due dates, but if it was going to scale, it needed a new way for people to discover and choose movies without physical browsing.

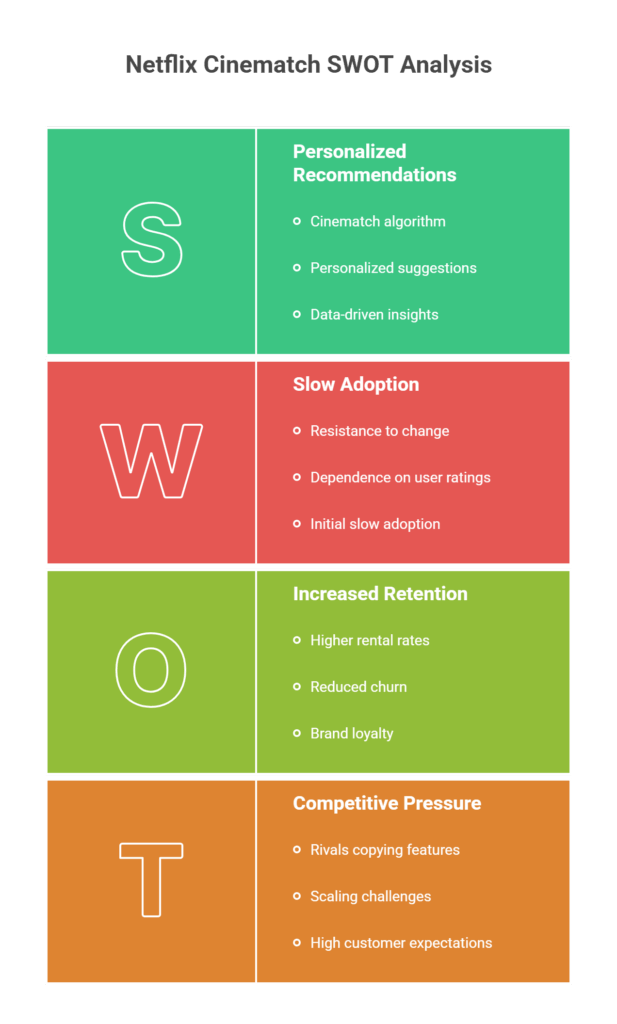

This need led to their algorithm, Cinematch, which matched your ratings against thousands of other customers to predict what you’d like next. In the early 2000s, most online stores arranged products alphabetically or lumped them into broad genres—helpful if you knew exactly what you wanted, less so if you were browsing for ideas. Cinematch acted as an early, practical use of personalization to replicate (and improve on) the store-browsing experience. It could bring up an under-the-radar film from a director you liked, surface a documentary with similar themes to something you enjoyed, or suggest a title you might never have found on your own.

The idea was straightforward: make finding the next movie as easy as possible. For customers, this eliminated the need to rely only on memory, chance encounters, or lengthy searches. For Netflix, it was a calculated attempt to replace a tactile habit with a digital process that felt just as personal. But like any new system, it met resistance. Customers were accustomed to trusting their own eyes in a store; trusting recommendations generated by code required a shift in mindset.

Other barriers came from the old routines themselves. Some people valued the trip to the store—it was spontaneous, a change of scenery, a social activity. DVD-by-mail required a bit of planning and trade-offs, including waiting for delivery. Even subscribers who liked the service sometimes let discs sit on the coffee table for days. Movie night was still treated as an event you planned for, not something that happened in passing. As a result, early use of recommendations was slower than the company hoped. If you’re leading change, don’t expect instant adoption—build simple substitutes for habits (like Netflix’s algorithm replacing browsing) and ask users to feed the system so it improves.

The numbers added urgency. While subscriptions were growing, some customers only rented one or two movies a month. For them, the flat monthly rate was more expensive than paying per rental. Profitability in the subscription model depended on higher turnover, meaning Netflix needed to encourage subscribers to watch and return discs more quickly. An easy, tailored discovery process was central to that goal.

As usage data accumulated, one clear pattern emerged: subscribers who engaged with recommendations rented more movies each month and were less likely to cancel. Personalized suggestions didn’t just entertain—they removed friction, which unlocked repeat behaviour. That meant subscribers saw more value and the business earned more from each customer. The insight was simple yet powerful: personalization could directly increase both rentals and retention. For managers, that’s a reminder to focus experimentation on points of friction that, once removed, encourage repeat engagement.

Netflix reinforced Cinematch’s value in multiple ways. Rating prompts appeared on the site. Emails included tailored suggestions. The “Movies You’ll Love” section took a prominent position on the homepage. All of this nudged users to interact with the system, which steadily improved its accuracy. The more customers engaged, the better their results, and the more they trusted it. Over time, what began as a functional tool became a defining part of the brand.

Early growth wasn’t dramatic. The algorithm’s impact showed up in small but steady gains. Recommendations became more accurate as the pool of ratings grew, and customer conversations began to feature phrases like, “Netflix recommended this and it was great,” generating organic promotion. Managers in any industry can see the parallel: adoption often starts slow, and the payoff may come only after enough use improves both the tool and users’ trust in it.

Behind the scenes, loyalty analysis confirmed the long-term benefits. Active recommendation users churned at far lower rates, lengthening their subscription lifetime value. This reinforced a key difference from the store-based model: instead of revenue spikes from punitive fees, income flowed from sustained satisfaction. Integrating personalization into the core service meant Netflix wasn’t just delivering DVDs—it was curating an experience tied closely to each subscriber.

This shift also hinted at a deeper advantage. Cinematch represented more than a feature; it was a step toward building a system that learned about the audience and adapted to them. Years before streaming, Netflix was already training itself to gather, interpret, and apply customer data at scale. That kind of adaptation, embedded in the relationship with the customer, is difficult for competitors to duplicate quickly.

Scaling this success would bring new pressures. More rentals meant the need for greater distribution capacity to keep delivery times short. A larger, more diverse customer base meant the recommendation engine had to handle bigger data sets and produce consistently relevant results. New subscribers arriving with high expectations wouldn’t forgive slow shipping or unhelpful suggestions.

The subscription plan and Cinematch had begun to redefine how people approached home entertainment. Removing late fees cut a major source of frustration, and personalized recommendations reduced the time and effort needed to choose a film. Together, they created an experience more convenient than the old model, without losing a sense of personal connection.

But competitive pressures weren’t going away. Larger players were watching, and the features that set Netflix apart were also the ones rivals could try to counter. The question was how long a smaller, more agile company could maintain its lead when the industry giant decided to respond.

And that was about to happen in a very public way.

Trials Against the Giant

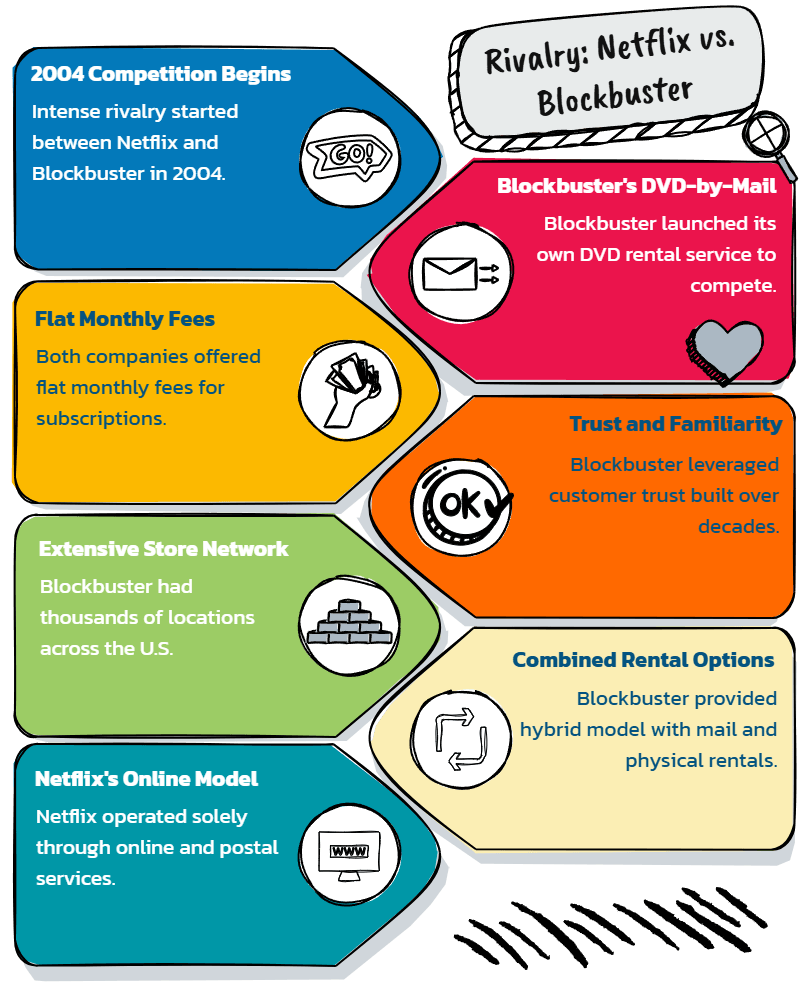

In 2004, competition between Netflix and Blockbuster became a head-to-head contest. Still the most recognized name in video rental, Blockbuster launched its own DVD‑by‑mail service. On the surface, it looked almost identical to Netflix’s offering—flat monthly fees, DVDs shipped through the mail, and online queues for picking titles. For customers who had spent years visiting their local Blockbuster, the new option felt immediately familiar. Netflix had worked hard to explain its model to the public; now Blockbuster could offer something similar and leverage the trust it had built over decades.

Blockbuster’s advantage was clear. It still had the largest store network in the industry and a much bigger advertising budget. Most people in the U.S. were within easy driving distance of one of its thousands of stores, which meant it could offer a hybrid model—DVD‑by‑mail alongside physical rentals. Netflix, in contrast, existed only online and through the postal system. Against a company with more than 9,000 locations, it still looked like the smaller, more vulnerable challenger.

As part of its online push in the mid‑2000s, Blockbuster also removed late fees from store rentals—a direct hit at Netflix’s most visible selling point. This was no small change. The absence of late fees had been a cornerstone of Netflix’s subscription appeal, attracting customers frustrated with paying extra when deadlines slipped. By matching that condition in stores, Blockbuster narrowed one of the clearest differences in the minds of renters. It was a move the company would later reverse amid mixed financial results, but in that moment it forced Netflix to rethink its messaging and retention strategy.

The impact was immediate. The emotional appeal of “no late fees” was less potent, so winning new customers required more effort and higher acquisition costs. The risk of churn grew: if subscribers saw two almost identical services and one was backed by a brand they already knew, switching became an easy choice. In a subscription model, losing customers means spending more just to keep numbers steady, which can quickly erode margins.

Competing on advertising or store presence was not realistic for Netflix. Instead, it doubled down on areas Blockbuster was less likely to prioritize. They focused on using customer data—rental history, ratings, and postal patterns—to make the experience faster and more personal. Postal analysis revealed where to locate new distribution centers so discs arrived sooner. Faster delivery meant people could watch and return movies more often, creating more value within the same monthly fee. At the same time, Netflix pushed users to rate titles, improving Cinematch’s recommendations, which kept customers engaged and made the service feel individually tailored.

This focus on delivery speed and personalization wasn’t accidental—it was chosen because these were difficult for Blockbuster to replicate at scale while still managing its sprawling store network. Improved infrastructure reduced wait times. Better recommendations increased rentals and strengthened loyalty. Together, they formed a competitive edge rooted in daily customer experience rather than price or brand heritage.

Netflix’s size made it easier to move quickly, but agility alone wasn’t enough. Operating with fewer layers of management allowed faster testing and deployment of ideas. For example, when data showed confusion about how to return discs, website prompts and packaging were adjusted within weeks. But this required discipline—every change had to scale without compromising service quality. For managers, this is the nuance: being small can help you react fast, but to grow successfully you must preserve the reliability that keeps customers.

The contrast between Netflix and Blockbuster at this point is a useful analogy for any leader. If you’re competing with a larger unit, find a capability they won’t prioritize and do it exceptionally well—Netflix chose personalization and delivery optimization. You can do the same by focusing on the one process your competitors underinvest in and making it your standout feature.

Gradually, these refinements began to show in the numbers. Despite Blockbuster’s late‑fee change and copycat service, Netflix’s subscriber base kept climbing. Retention improved as fast delivery and tuned recommendations removed reasons to leave. Positive customer experiences fueled word‑of‑mouth growth. Blockbuster’s hybrid model and brand recognition had given it an early boost, but Netflix’s targeted improvements chipped away at the perception gap.

Eventually, Netflix pulled ahead in online subscribers—a milestone that signaled more than just a numeric lead. For customers, it reframed Netflix as the default name in DVD‑by‑mail, even over the industry giant. For Netflix, it confirmed that improving speed, personalization, and overall ease of use could beat sheer brand size. Yet this wasn’t an excuse to ease off. Blockbuster still had enormous resources and could alter its strategy again.

Inside Blockbuster, attention was split. Stores remained the primary revenue source, but growth was clearly online. Maintaining quality in both channels at once proved a challenge. For Netflix, this division of focus bought room to keep honing the online service without competing directly on physical store operations. The head‑to‑head battle was no longer just about matching features—it was about who could manage their chosen model with more consistency and value for the customer.

This period underscored a broader strategic point. In markets dominated by a large player, imitation is tempting but rarely enough. Netflix didn’t try to be Blockbuster Lite. It concentrated on elements that were both strategically important and operationally underdeveloped in its rival. The lesson extends far beyond entertainment: position yourself where the leader is weakest and work relentlessly to be best in class there.

When Netflix overtook Blockbuster in online subscribers, it was the outcome of focus and adaptive execution, not just the benefit of being lean. The challenge from Blockbuster’s late‑fee removal had forced them to clarify their strengths and refine the user journey. Blockbuster still held the upper hand in many measures, but the rental market’s balance was shifting.

While Netflix was winning ground in DVDs‑by‑mail, its leadership knew that no delivery system was immune to disruption. The abilities they were sharpening—fast adaptation, strategic use of customer data, and investment in service quality—were portable skills. Outperforming on delivery bought Netflix time, but the next change was already forming on the horizon, and it wouldn’t be about discs at all.

The Leap to Streaming

By 2007, Netflix saw an opening to test a very different way for customers to watch. Broadband internet was becoming more common in U.S. homes, and short online videos on platforms like YouTube were gaining popularity. The idea was simple: instead of waiting for a red envelope to arrive, what if subscribers could watch instantly, with no packaging, mailing, or returns? It was a shift that could remove the biggest physical constraint on their service.

The promise was significant, but streaming full-length movies to thousands of people at once was far more complex than hosting short clips online. Speeds varied widely between households, and in many areas broadband was still too slow to guarantee smooth playback. On the technical side, both Netflix’s servers and customers’ devices had to deliver uninterrupted viewing. A single delay or prolonged buffering could drive people away. Uneven broadband quality wasn’t just a technical hurdle—it was one reason Netflix deliberately kept the DVD service running as they trialled streaming. Maintaining DVDs safeguarded revenue while giving the new model time to mature.

In January 2007, Netflix launched “Watch Now” to its U.S. subscribers. At first, it offered fewer than 1,000 titles, streamable only on a computer. It came at no additional cost to existing plans, a decision aimed at lowering the barrier to trying the feature. Compared to the DVD library, the selection was small, and video resolution was limited by home internet speeds. But the goal wasn’t to match the DVD experience instantly—it was to gather data on how customers interacted with streaming and to understand the technical demands at scale.

For most at the time, streaming felt like an optional extra. Subscribers valued the breadth of the DVD library and were accustomed to planning viewing a few days ahead. While streaming removed the wait, it also meant fewer choices for newer or high-demand titles. Some tried it out, then returned to DVDs for the bulk of their viewing. Habits rooted in physical media were not going to change overnight.

Hardware created another obstacle. In 2007, most televisions weren’t internet-ready, so streaming meant watching at a desk on a smaller computer screen. That gap between where people preferred to watch and where streaming was available slowed adoption. Broadening access to the living room was essential if streaming was to compete with DVDs as the default viewing method.

Netflix solved this by working with other companies instead of building its own devices. They struck early deals to integrate their service into popular hardware, starting with gaming consoles like the Xbox 360 and expanding to Blu-ray players and dedicated streaming units. Very quickly, subscribers could use devices they already owned to stream Netflix on their TV. The move bypassed the cost and complexity of hardware development while removing a major barrier to living room adoption. For managers, the lesson is clear: if your success depends on an ecosystem, secure lightweight partnerships early so you don’t carry the full burden in-house.

Balancing the old and new models was a constant leadership question. Putting too much emphasis on streaming could hurt the DVD business before it was safe to scale it down. Moving too slowly risked losing a first-mover advantage to competitors. Including streaming within existing subscription tiers helped manage this tension. Customers didn’t have to choose between two different services—both were available side by side.

Early data from “Watch Now” users offered encouraging signs. Even with the smaller catalog, those who tried streaming often kept using it. The instant access prompted more spontaneous viewing, increasing overall engagement. Usage patterns also hinted at a stronger retention effect: once integrated into a customer’s routine, streaming made the service harder to give up. Eliminating the shipping step seemed to tighten the connection between the customer and the brand.

An additional benefit was economic. Each title streamed was one less disc to purchase, handle, and ship. At scale, this reduced many of the variable costs that had shaped the DVD business. It also sidestepped the inventory limits of physical media; a disc could only be in one place at a time, but a digital file could be streamed by thousands simultaneously. This realization supported larger investments in both streaming technology and licensing content.

For customers, streaming changed the nature of access. Choosing a title could lead to watching it within seconds. There were no queues to build around mailing schedules, and no concerns about a title being out of stock. That level of convenience was difficult for any physical rental model to match. But building it into a mass-market service required not just the technology to perform well, but also a much larger, well-licensed selection.

Keeping the early streaming library small was a conscious choice. It limited the technical and reputational risk while Netflix learned how to maintain consistent quality over different networks and devices. Problems in playback or availability could frustrate customers, but affecting only a small part of the service protected the overall brand. As confidence in the delivery system grew, so did the case for expanding the catalog.

During this time, customer behavior showed a split. People with slower internet often continued to favor DVDs, while subscribers with faster connections—and compatible devices—shifted more viewing to streaming once it was available in their living rooms. This reinforced that the transition would be gradual, shaped by both infrastructure and habits. Managing both businesses in parallel remained critical to retaining customers throughout the change.

The retention benefit was too strong to ignore. Subscribers who used streaming were less likely to cancel, and in a subscription business, retaining a customer for just a few extra months could have a large impact on revenue. Streaming had started as an experiment, but these results moved it to the center of Netflix’s strategic planning.

By the end of this early phase, Netflix was no longer just a DVD provider experimenting with digital delivery—it was positioning itself as a platform for on-demand viewing. The technical proof was there, customer adoption was growing, and device integration had made streaming part of the living room experience. The question had shifted from whether streaming could work to how quickly it should be scaled.

The next barrier wouldn’t come from technology or hardware access but from the content itself. As more people streamed, the importance of the available library became sharper. Unlike DVDs, streaming rights depended on specific licensing deals, and competition for those would intensify as other companies entered the space. Streaming had effectively solved the distribution challenge, but controlling what viewers most wanted to watch would become the larger competitive ordeal ahead.

Facing the Ordeal of Content

For Netflix, gaining ground in streaming brought a new challenge into focus: if the titles subscribers valued most were controlled by other companies, the platform’s position could be undermined overnight. Without exclusive shows and films, Netflix risked being seen as just another delivery outlet for content others owned. The moment studios chose to keep their own productions or license them to rivals, large parts of Netflix’s library could disappear. As more players entered the streaming market, that risk grew.

The logical defence was to own more of what it offered. Exclusive rights would keep high-value titles on the platform indefinitely and allow Netflix to align its catalog with viewing trends without depending on outside negotiations. But originals came at a high cost. Producing a series or film meant investing heavily in writing, casting, filming, editing, and marketing before there was any proof of audience appeal. If a project failed, the loss could run into millions. For managers, the direct takeaway is clear: control your supply chain where possible—if licences can be pulled, consider producing or owning the capability that ensures continuity.

Competing with long-established studios required more than a few experiments. It demanded building a steady pipeline of quality programming year-round. This meant shifting from a tech-focused distributor to also running a full-scale production operation. Netflix had been in the business of delivering other people’s work efficiently; now it needed to originate content at a high standard, repeatedly.

A turning point came in 2013 with the release of House of Cards. This political drama was distributed in an unconventional way for the time: the entire first season was made available at once, so subscribers could watch on their own schedule. The show earned both critical and popular praise. It proved that streaming could be the primary home for big-budget, high-calibre productions and, crucially, it drove new sign-ups while giving existing customers a reason to keep their subscription active.

That success established a model Netflix would replicate. In the years that followed, it increased its spending on original content at a rapid pace. By 2020, Netflix was investing roughly $17 billion a year in content, putting it alongside the largest entertainment players in the world. Originals became central not just to filling the library but to creating attention-grabbing moments that anchored the brand in cultural conversations and fostered long-term loyalty.

Producing at that scale required major organisational changes. Netflix had to cultivate strong relationships with writers, directors, performers, and production crews across multiple continents. It needed systems capable of managing numerous big-budget projects simultaneously. There was also a constant balancing act between volume and quality: too few standout releases risked cancellations after a show ended; too many weak titles risked damaging the brand.

Global expansion intensified the complexity. A growing share of Netflix’s audience was outside the United States, bringing different tastes and cultural expectations. What worked well in one market might fall flat in another. To reach these viewers, Netflix began investing in originals in local languages, such as Money Heist from Spain and Sacred Games from India. These productions appealed to domestic audiences and, in some cases, broke out internationally. For managers, the point is practical: to grow across diverse markets, consider localising offerings rather than relying solely on a single headquarters-driven product.

This upstream investment strengthened Netflix’s control over its most critical resource. By producing and owning its shows, it could protect them from being withdrawn due to shifting licensing deals and ensure they were available worldwide. It was the entertainment equivalent of securing a key supply line in manufacturing—removing a dependency that could limit growth.

The rewards were clear in 2016 with Stranger Things. Combining science fiction, horror, and 1980s nostalgia, it attracted viewers across different age groups and became a global talking point. Merchandise, events, and social media discussion extended its presence well beyond the episodes themselves. It showed that the right original content could add value far beyond the immediate watch, encouraging subscribers to stay engaged and enticing new customers curious about the phenomenon.

Cultural hits like this also made business sense. Every must‑see title increased the perceived value of staying subscribed. Originals remained part of the library indefinitely, attracting new viewers long after their debut season. Over time, Netflix built a bank of valuable assets that generated ongoing returns without the recurring costs of licensing.

Not every project succeeded. Some series didn’t find an audience, fading quickly from relevance. This was a calculated part of the approach: producing at scale inevitably meant some misses. The role of leadership was to ensure that enough projects connected strongly with viewers to justify the overall spend. Data analysis informed renewal and cancellation decisions, focusing resources where they were most effective.

This move into original production also altered Netflix’s position in the industry. It was now in direct competition with film and television studios for creative talent, awards, and audience share. That required creating an environment where artistic ambitions could align with business goals like retention and growth. Too much interference could alienate creators; too little oversight could drive up costs without results.

For subscribers, originals became the most recognisable part of the Netflix brand. While third‑party films and shows still had a place, the programs most often discussed and shared were increasingly those exclusive to the platform. Even if other services offered similar licensed content, they could not match Netflix’s unique catalog without negotiating directly for it.

Owning the rights to these productions offered structural marketing advantages. Netflix could promote its originals worldwide without dealing with the regional restrictions typical of licensed content. Campaigns could launch to all territories at once, amplifying impact and synchronising audience engagement. Specials and niche shows could find larger audiences by being instantly accessible in multiple countries.

Some non‑English‑language originals reached global popularity, propelled by dubbing and subtitling. This underscored a change in viewing patterns—audiences were more open to stories from different cultures as long as the delivery was seamless. For Netflix, the borderless nature of streaming meant a surprise hit in one country could scale to global proportions.

As more competitors launched streaming platforms and reclaimed their own licensed content, Netflix’s broad library of originals became a key defensive asset. These shows and films couldn’t simply be pulled by licensors, allowing the company to maintain a stable selection while others were dealing with shifting rights.

The financial commitment was significant, but so were the strategic benefits. Sustaining this level of content production required confidence in both subscriber growth and the retention power of originals. The alternative—remaining heavily dependent on external suppliers—would have left the company vulnerable to rivals controlling the most in-demand titles.

By building its own creative pipeline, Netflix had redefined itself. It was no longer only a technology-driven distributor. It was now a major entertainment producer, competing for audience attention at the highest level and blending creative output with technological reach. Its competitive strength came from the blend—owning both the means of distribution and much of the content being distributed.

Keeping that formula effective was its next leadership test. Large-scale original production brought pressures to innovate, manage costs, and react quickly to shifting viewer preferences. It also highlighted the need for a company culture capable of making bold moves, testing ideas, and adjusting course without undermining trust.

And just as Netflix was building that balance, the company faced a decision that would test not only its strategic thinking but also how it communicated change to its customers.

The Qwikster Misstep

In 2011, Netflix made an announcement that took many of its customers by surprise. The company said it would split its DVD‑by‑mail and streaming services into two separate brands. Streaming would stay under the Netflix name, but the DVD business would move to a new brand called Qwikster. Along with that split came a requirement for customers who wanted both services to pay for them separately, leading to a higher combined monthly cost than before.

Until then, subscribers had grown accustomed to managing both DVDs and streaming from one account—a single sign‑in, one library, and a single monthly bill. Under the new plan, those conveniences would be replaced with two different websites, two queues, and two charges. Anyone using both DVDs and streaming would have to move between them to manage their viewing. This wasn’t just a rebrand. It altered the customer experience every time someone wanted to watch something.

The Qwikster name itself caused problems. It was unfamiliar, had no clear link to Netflix, and lacked any established brand equity. Many subscribers said they didn’t immediately connect the new name to the DVD‑by‑mail service they had been using for years. The announcement also landed poorly in terms of timing. Earlier in the summer, Netflix had already raised subscription prices. Now those same customers were being told their service would be split in two.

Backlash was immediate. Online forums and social media posts showed frustration not only about the higher price but also the inconvenience of dealing with separate accounts. The press echoed that sentiment, portraying Qwikster as a decision made without considering how people actually used the service. Netflix’s signature simplicity—streaming and DVDs combined—was being undermined in a visible way. This is a classic example of a change that made sense internally but increased customer friction. Always map operational benefits to lived customer experience before rollout.

The business impact came quickly. Some customers canceled one of the services; others left entirely. Churn rates—the share of subscribers leaving each month—jumped. The company’s stock price dropped sharply as investors reacted to the sudden slowdown in growth and weakening sentiment. In just a few short weeks, Netflix’s positive momentum around streaming had been interrupted.

Inside Netflix, the reasoning had been straightforward. The DVD business was slowly declining, while streaming was expanding quickly. Running them separately could let each be managed more efficiently and help prices better reflect usage. On paper, this was a sound operational plan—yet in practice, it broke a connection that customers valued. Many subscribers relied on streaming for instant access and DVDs for harder‑to‑find titles. Keeping everything in one place was part of the promise. Removing that link increased friction at a time when competitors were focused on making viewing easier.

Reed Hastings, Netflix’s CEO, quickly saw how far the reaction had gone. Within a month of the Qwikster announcement, the decision was reversed. Both services would remain under the Netflix name, and subscribers would continue managing them from one account. Hastings issued a public apology, acknowledging that the company had underestimated how negatively customers would respond. The reversal sent a clear message: decisions that harm core user experience would be undone. If you misread customers, own it quickly—public restitution can limit long‑term damage.

From a leadership perspective, speed mattered. Leaving the change in place for months could have deepened losses and resentment. The company could not undo the earlier price increase, but it acted to keep the combined platform intact. This prevented further erosion of trust and stopped the disruption from becoming a long‑term brand problem.

For managers, Qwikster is a reminder that internal logic does not guarantee external acceptance. A staged rollout and pilot approach should be standard for any disruptive change. Test with a small group, collect qualitative and quantitative feedback, and refine both the product and the messaging before a full public launch. This not only exposes potential friction points but also gives teams a chance to adjust before they affect the entire customer base.

Operationally, Netflix treated Qwikster as an internal case study on assumption‑testing. Usage data and revenue models had been accurate, but the company had weighed operational efficiency more heavily than customer acceptance. Without testing or gradual introduction, they missed the emotional impact of altering how people accessed their content. Communication also played a role. Announcing the change in a single, sweeping message left little room to respond to feedback before rollout.

The reversal shifted focus back to building the streaming business. But the company now had better insight into the pace and presentation of major changes. Customers had signaled clearly that they would tolerate disruption only if they understood the benefit and if the transition was easy to manage.

It’s worth asking yourself a question here: How would your team respond if a major change caused immediate customer churn? Do you have a recovery plan and a clear process for escalating such issues? Having this prepared can mean the difference between a controlled course correction and lasting damage.

For Netflix, the damage was real in the short term—subscriber losses, lower stock value, and a bruised reputation. Yet the quick reversal contained the fallout. Customers saw a willingness to listen and act, which preserved enough goodwill to keep the company’s subscription growth on track. Admitting error publicly became part of how the brand framed its relationship with its audience.

This misstep didn’t slow Netflix’s appetite for taking risks. It did, however, add discipline to how big changes were introduced. Future shifts tended to come with clearer explanations, more emphasis on the customer benefit, and, in some cases, incremental releases rather than abrupt nationwide changes. The company had learned that change management was as important as the change itself.

For other organizations, this is a pointed reminder: major shifts can be successful even if they disrupt routines, but they have to be introduced in ways that give customers time to adapt. Monitoring early feedback and being ready to adjust or reverse course can protect long‑term relationships that might otherwise be lost.

The Qwikster episode became a small but visible counterpoint in Netflix’s history. In a record of big bets—DVD‑by‑mail, streaming, original content—it was a rare public error. But because it was corrected quickly, it became another proof point that experimentation carries the possibility of mistakes, and that adaptability is just as critical as vision.

In the end, the event reinforced the balance Netflix needed to sustain as it grew: move decisively on innovation, but never so fast that the customer experience is undermined. That balance would depend not just on strategy, but on the mindset and culture of the people inside the company—a foundation for change that went beyond any single product decision.

Building a Culture for Change

Strong strategic moves alone won’t drive transformation if the internal environment can’t keep pace. Netflix invested heavily in building what it calls a culture of “Freedom and Responsibility,” designed to sustain speed and adaptability over the long term.

Some of its workplace policies sound unusual from the outside. Employees take vacation without tracking days. Expense approvals boil down to one guideline: “act in Netflix’s best interests.” There’s no thick rulebook defining every situation. The aim isn’t informality for its own sake—it’s to reduce friction in decision-making so the company can adapt quickly.

At the core is the principle of Freedom and Responsibility. The freedom is trust to make decisions without layers of approval. The responsibility is owning the result, whether it succeeds or fails. In practice, this only works if people are exceptionally capable, aligned on goals, and able to work without constant oversight. The takeaway: freedom speeds decisions; responsibility ensures those decisions stay grounded in results.

This approach depends on what Netflix calls “high talent density.” The company hires fewer people but expects nearly all to be top performers in their role. Talented people can make informed decisions without being tightly managed. But here’s the trade‑off—expectations are higher and underperformance is addressed directly. The caution for managers: without high talent density, the same model can break down fast.

To maintain those standards, managers use the “Keeper Test”—asking themselves, “Would I fight to keep this person if they were leaving?” If the honest answer is no, it’s a signal the employee may not meet the performance bar. This keeps teams strong and reduces the need for guardrails. It also means quick, sometimes uncomfortable decisions to part ways when fit isn’t there. The takeaway: high talent density reduces the need for control systems because you trust the judgment of those in the role.

Another pillar is radical transparency. Rather than restricting sensitive information to executives, strategy, performance data, and key decisions are openly shared across the company. This ensures employees have the same context as leadership and can act on it. Netflix calls this “context, not control”—leaders provide the background and objectives, but the how is left to the team. The takeaway: transparency sharpens judgment and reduces hesitation.

This openness extends to failures. When a bet doesn’t pay off, the process and outcome are shared internally in what’s nicknamed “sunshining.” These candid post‑mortems allow everyone to learn from mistakes and avoid repeating them. The takeaway: visible lessons from failure normalise learning and make people more willing to try new things.

Autonomy is reinforced through practices that promote rapid, low‑cost experiments. Teams don’t need senior sign‑off to run small tests. If an idea looks promising—like a new recommendation layout—it can be trialled with a subset of users, producing fast data on whether it works. If it fails, the cost is low; if it succeeds, it scales. This mirrors how Netflix rolls out product features and marketing tweaks. The takeaway: tight feedback loops allow faster, more precise responses to change.

For managers wanting to apply this, try a one‑month pilot. Select a capable team, remove one specific approval step, track decision speed and error rates, and then decide whether to expand it. This time‑boxed approach mirrors Netflix’s test‑and‑learn habit without overexposing the business.

Some leaders hesitate to introduce policies like unlimited vacation or no‑approval expenses, fearing misuse. Netflix offsets that risk by pairing freedom with accountability, high performance standards, and constant alignment on goals. In other words, these policies work because of the system around them, not in isolation.

Combining freedom, responsibility, talent density, transparency, sunshining, and experimentation fosters a workplace where change is routine rather than disruptive. Innovation isn’t siloed to a single department. A content producer, engineer, or marketer can run with an idea because they have the autonomy to act and the information to decide. The takeaway: broadening who can innovate increases organisational capacity to adapt.

For leaders, the operational benefit is less micromanagement. When people have high capability and clear context, more initiatives can run in parallel without bottlenecks. Mistakes aren’t career‑ending—they’re surfaced, analysed, and used for improvement. That resilience is essential when conditions change quickly.

This model does need active upkeep. Maintaining high talent density involves recruiting carefully, evaluating performance consistently, and addressing misalignment promptly. Radical transparency requires disciplined communication so information is accurate and understood. Freedom and responsibility demand ongoing reinforcement of priorities so decisions stay aligned to strategy. Let these slip, and autonomy can drift into inconsistency or paralysis.

The lesson for other companies is not to copy Netflix’s policies blindly. Instead, align three elements: capable decision‑makers, high‑quality transparent information, and systems that reward initiative while holding people accountable for results. Without alignment, giving more freedom can slow things down instead of speeding them up.

One advantage of this cultural model is preparedness for the unplanned. If an opportunity or threat appears suddenly, organisations with rigid approval chains often pause while processes catch up. In an environment like Netflix’s, someone close to the issue can act immediately, with leadership stepping in to refine rather than initiate. That speed can make a competitive difference.

Culture also shapes the sustainability of change. Netflix doesn’t need to build new decision processes for each challenge—they already operate within a framework that supports acting on new information and iterating quickly. Change is something the organisation is trained to handle, which lowers the disruption cost.

This cultural consistency has carried the company through multiple strategic shifts—moving from DVDs to streaming, growing original content production, expanding globally, and enhancing product features. The same practices keep different phases of the business aligned and adaptable.

The balance that sustains this is autonomy within a shared direction. Employees have room to innovate and authority to decide, but they operate with clear understanding of company priorities. This alignment keeps initiatives pulling in the same direction without constant oversight.

In essence, Netflix has deliberately shaped an environment built for continuous transformation. Every cultural element reinforces the ability to act quickly and effectively as conditions change. For companies facing frequent or unpredictable change, culture isn’t an optional layer—it’s the engine that makes continued adaptation possible. You can win once with a lucky move, but you stay competitive by building a team and system that can adapt repeatedly.

That readiness has been as critical to scaling as any specific strategic choice. Yet while a responsive culture can steer the company’s direction, making that direction work in practice relies on equally strong support systems beneath it. And Netflix’s ability to deliver an evolving service to millions at home and abroad has also depended on something less visible but just as decisive: the technological foundation that keeps the experience consistent, no matter how the business changes.

Technology as the Invisible Enabler

When Netflix first moved into streaming, the technical challenge was manageable. Most of its users were in the United States, and the library of available titles was small compared to today. But as subscriptions climbed and streaming overtook DVDs as the main viewing method, the demands on its systems increased sharply. Delivering video in near‑real time to millions of people across continents isn’t the same as sending a short message or loading a simple web page. Video delivery depends on sustained bandwidth, low latency, and rapid recovery from interruptions. The infrastructure they started with would not scale indefinitely.

A pivotal moment came in 2008, when a major database outage took the DVD rental system offline for days. That incident confirmed that if streaming was to grow globally, Netflix needed a far more resilient and flexible platform. The company began a staged migration to Amazon Web Services (AWS), moving off its own data centers toward a cloud‑based setup. This process stretched over several years, with core systems running in the cloud by the mid‑2010s. Migrating to AWS wasn’t just a hosting change—it allowed Netflix to expand capacity quickly during peaks, like when a new season of a popular show dropped, and then reduce it when demand eased. Investing in flexible infrastructure like cloud and a content delivery network costs more upfront but reduces the marginal cost and risk of scale later.

Cloud made scaling compute and storage more responsive, but content still had to travel to users efficiently. Routing everything from central servers through public internet paths created delays and variability in quality, especially for viewers far from main hubs. To address that, Netflix built its own content delivery network, Open Connect. Starting in 2012, the company began placing Open Connect servers loaded with frequently watched titles inside internet service providers’ networks. That local cache model sharply reduced latency and eased the strain on upstream internet routes. A show you watch is streamed from the closest Open Connect server rather than from the other side of the country or beyond.

This design improves start times and minimizes buffering, but its strategic value runs deeper. By controlling distribution through Open Connect, Netflix can keep user experience consistent even where general internet infrastructure is uneven. That consistency is critical in building trust. Small changes in availability matter—a move from 99% uptime to 99.99% might sound minor, but it drastically reduces perceived outages. For a subscription business, that difference can separate satisfied customers from widespread cancellations.

The engineering choices also built in redundancy. In streaming terms, redundancy means having backup systems that take over so seamlessly that viewers never see an interruption. Netflix layers this at multiple points: within AWS regions, across AWS regions, and at the level of Open Connect itself. If part of the system fails, traffic reroutes automatically. For customers, the effect is a show that keeps playing without a hitch. For managers, the takeaway is clear: Can your stack scale globally without a full re‑architecture? If not, what minimal investments buy the most future‑proofing?

These infrastructure moves positioned Netflix to expand internationally at a pace that would be difficult for companies tied to physical servers in each market. When launching in a new country, the groundwork was often already in place: AWS capacity available in region, and Open Connect boxes installed with local ISPs. That let Netflix enter markets in weeks or months instead of years, and with predictable streaming quality from day one. It turned what could have been a long build‑out into a mostly coordination and licensing exercise.

For leadership, the strategic benefit is speed and flexibility. If product or content teams want to add a new feature requiring more processing—personalized recommendations that use heavier analytics, for example—the cloud allows bolting on that capacity without a physical hardware cycle. If a marketing plan calls for a simultaneous global launch, Open Connect helps ensure that sudden traffic surges don’t choke performance. Infrastructure enables strategy when it removes delivery as a limiting factor.

It also works in reverse: strong infrastructure reduces the need for constant firefighting, freeing teams to focus on innovation. Content creators can plan ambitious releases without worrying whether the system will handle demand. Product managers can test interface changes with global audiences without risking a crash. The separation of creative and delivery concerns allows each side to operate at full speed.

Some companies underestimate this link. They see infrastructure as a cost center to minimize rather than as a growth enabler. In reality, weak infrastructure quietly caps the scale of ideas. At smaller volumes this isn’t obvious; the first sign might be a major outage or a failed launch. By then, rushed fixes are expensive and publicly visible. Netflix avoided this trap by making major technical investments well before they became strictly necessary, absorbing the higher early cost in exchange for smoother scaling later.

While these decisions rarely make headlines compared to hit shows or new pricing tiers, they form part of the invisible contract with customers: the platform will work when you want it. That contract builds loyalty as reliably as content catalogues do. From a managerial view, the lesson is simple: infrastructure choices are not back‑office details—they are strategic enablers.

Once the AWS migration and Open Connect network were established, Netflix could maintain very high uptime even as total viewing hours climbed. Those extra decimal points in availability meant people kept using the service without thinking about uptime at all. The absence of frustration kept cancellation rates lower. In subscription services, the cost of avoiding churn often outweighs the new customer acquisition drive.

Global reach also grew in step with infrastructure capability. Netflix went from serving a few dozen countries to over 190 in just a few years. Such rapid scaling would have been risky without a backbone that could deliver reliably across very different network conditions. Because performance was consistent, Netflix could market aggressively in new territories without damaging the brand through uneven service.

The Open Connect model gave an additional edge: better relationships with ISPs. By placing content closer to the end user, Netflix reduced upstream bandwidth demands. ISPs benefited from less strain on their networks, and users benefited from faster, clearer streams. This alignment of incentives smoothed expansion into markets where local regulations and partnerships could otherwise slow entry.

For companies plotting similar expansion, the managerial point is to consider infrastructure design early in the growth plan. Ask whether the current systems make entering multiple regions possible without repeating major builds. If not, identify the smallest set of capabilities—redundancy, elasticity, local delivery—that would have the biggest scaling effect. This prioritization avoids overbuilding while removing the biggest growth bottlenecks.

The result for Netflix was a delivery system that could support continuous change. The technical base didn’t just keep existing services running; it enabled rapid iteration in product, content, and geography without constant re‑engineering. Strategic moves like releasing original series globally on the same day or adding new personalization features would have been slower, riskier, or impossible without this groundwork.

By the time competitors like Disney+, Amazon Prime Video, and Apple TV+ began vying for market share, Netflix already had years of global infrastructure experience. Its ability to coordinate worldwide launches, maintain stable performance under peak loads, and reach viewers with minimal local delays became a competitive shield. Others could match content investments, but matching a mature, distributed delivery network took time.

Infrastructure rarely excites customers directly, but they notice when it fails. Netflix’s approach demonstrates that for digital services, the invisible enabler—cloud flexibility combined with local delivery through its own CDN—can define whether strategy scales successfully. The business lesson holds whether you’re running a media platform or another service: invest early enough that growth does not outpace your ability to deliver.

With that enabler in place, Netflix could focus on the visible battles: building a global brand, expanding its content, and competing for customer attention in an increasingly crowded streaming market. And as the service evolved from a U.S. DVD‑by‑mail startup into a worldwide producer and distributor, the question moved from how to deliver content reliably to how to maintain its edge in a market where everyone was now playing the streaming game.

The Return with the Elixir

In 1999, Netflix was a small DVD‑by‑mail business more concerned with staying afloat than reshaping an industry. By 2020, it had become a global platform producing and distributing some of the most‑watched shows and films in the world. The leap from a few rented discs to simultaneous releases of originals in over 190 countries was more than a product shift—it was a complete reinvention of the business. Few companies sustain that level of transformation over two decades and hold their lead.

By then, the streaming landscape had shifted dramatically. In its early online years, Netflix had few direct competitors. By 2020, services like Disney+, Amazon Prime Video, and Apple TV+ were operating at global scale, armed with deep content libraries, brand power, or extensive technology ecosystems. Competition was now as much about winning viewer attention and retaining talent as it was about adding subscribers.

With more credible alternatives in the market, a broad library alone was no longer a growth guarantee. Switching between services carried little cost beyond a monthly fee, so Netflix had to create new incentives to attract untapped users. One example came when, in late 2022, Netflix introduced a lower‑cost ad‑supported plan to capture more price‑sensitive customers. The reduced price opened doors in markets where standard rates had slowed adoption. The trade‑off—advertising during shows and movies—marked a notable shift for a company that had built much of its brand on ad‑free viewing. It signalled a willingness to adjust principles in response to changing market and audience conditions.

That decision offers a broader lesson: as markets mature, the model that fuelled early expansion may not be enough to keep adding customers. Reaching new segments often requires modifying the product, price point, or business approach. It doesn’t have to mean abandoning core strengths, but it does mean creating options for people who previously stayed out of reach. The persistent challenge is to do this without undermining what existing customers value.

Through the lens of the Hero’s Journey, this is the “return with the elixir.” The protagonist comes back from trials with a gift for the community. In Netflix’s case, the gift is not a single product but a set of repeatable capabilities earned through crossing multiple thresholds: anticipation of change, experiment‑driven learning, and infrastructure plus culture to scale. Managers can treat these as a framework—three points to recall and apply—whenever competitive or market pressure builds.

One of the most valuable patterns has been anticipating change before the current model runs aground. Netflix moved toward streaming before physical rentals dropped everywhere, and invested in original content before licensing restrictions became severe. Acting ahead of obvious necessity gave it control over timing and direction. In business terms, it’s easier to run pilot projects, correct mistakes, and refine execution when you’re not already in a defensive position.

The discipline to anticipate rather than react can be applied well beyond media. It comes from structured observation of customer behaviour, technology trends, and competitors’ strategic moves, combined with a willingness to invest in unproven but strategically consistent ideas. Without that discipline, companies risk racing to imitate changes others have already mastered—usually a losing position.

The second capability—the habit of experiment‑driven learning—has been visible across Netflix’s history. From testing flat‑fee DVD subscriptions to refining recommendation algorithms, from trialling interface layouts to experimenting with release schedules, the company built small‑scale tests into its operating rhythm. Experiments that worked could be expanded; those that didn’t were dropped without fear of damaging the brand. This process created a low‑risk path to gather evidence before committing at scale. For managers, a concrete prescription is to make reinvention routine: dedicate a small, recurring budget to exploratory pilots and set a lightweight governance process to kill or scale them.

The third is the pairing of infrastructure and culture to scale. Whether it was building a global content delivery network before expanding streaming internationally or fostering a culture of transparency and accountability to speed decisions, Netflix treated readiness as a strategic objective. The visible moves—the product launches, interface changes, or new content—were supported by less visible systems that reduced friction and kept service quality consistent during change. This is a reminder that without underlying capacity, even the best ideas can falter when they meet execution.

In a crowded market, retention becomes as important as acquisition. Netflix leans on its recommendation system, personalisation in marketing, and a steady release flow to keep customers engaged month after month. Each of these reduces the temptation to pause or cancel, preserving revenue without heavy discounting. The same tactics—know your customer patterns, keep delivering relevant value, and close engagement gaps—apply in any subscription‑based or relationship‑driven business.

For organisations studying this arc, the strategic takeaway is that reinvention needs to be a standard operating practice, not a crisis measure. This means carving out resources to explore emerging opportunities even when the current model is profitable. It also means introducing change in stages rather than in abrupt, market‑wide leaps that carry higher risk. When you make small adjustments part of the normal rhythm, transformation feels less like a disruption and more like the next iteration.

Netflix’s “return with the elixir” is therefore a method of operating: anticipate, experiment, and support change with systems and culture that allow scale. These three capabilities fuel leadership in fast‑moving markets where advantage erodes quickly. They are portable, applying as well to manufacturing, retail, or technology services as they do to entertainment.

Even as competition intensifies, those capabilities allow Netflix to keep evolving—from adding new pricing models to producing both global blockbusters and local language hits—without waiting for external forces to dictate the terms. The company has accepted that the next disruption could come from its own initiatives as easily as from a rival, and prepares for both scenarios.

In practical terms, applying this in your own context begins with questions. What assumptions about your customers, your market, or your product mix could realistically shift in the next few years? If one of those changes happened, how would you respond? And more importantly, what could you put in place now—in skills, in processes, or in infrastructure—that would make your response faster and more effective?

The arc from a niche DVD rental service to a global media leader is compelling because it proves that repeated, intentional adaptation can reshape an entire industry. The essential themes—anticipating the next turn, learning through controlled experiments, and creating the internal conditions to execute at scale—are universal. Any organisation facing unpredictable markets can borrow from this approach.

The payoff is an advantage that compounds over time. Products, services, and even industries will change, but the competency to change deliberately and effectively becomes its own moat. With each successful shift, the organisation builds more capability for the next one, making it harder for competitors to catch up.

As Netflix moves forward, the context will keep changing, but the working method remains stable: keep scanning the horizon, prepare for multiple possible shifts, act before change becomes unavoidable, and maintain the internal conditions to adapt repeatedly. That formula turns volatility into a manageable, even strategic, resource.

So, ask yourself: What assumption about your customers could change next, and what small test would you run this week to be ready?

Conclusion

Transformation isn’t about avoiding mistakes. It’s about learning from them faster than others and using that knowledge to adapt quickly.

Identify one entrenched rule—run a two‑week pilot to replace it with one experiment. Ask your team the Keeper Test on one role this quarter and act on any gaps. Run one small A/B test this month to remove a customer friction point.

Choose one of these and start within the next 48 hours. In the comments, name one rule in your organisation you’d flip this month and why. Then see what changes when you take that first step.